Before “wireless” meant a Wi-Fi router in your home or office (the “Wi” is for wireless), it meant “radio” in radio’s early days, in the 1920s. “Turn on the wireless, Sweetie.” And before that, it was the word that a number of 19th century European physicists were using for an idea that led to practically all modern communication – electro-magnetic radio waves.

One of the most unusual and important of these physicists was Guglielmo Marconi, born in 1874 in a Baroque mansion we visited yesterday in the heart of old Bologna, Italy. This building is called the Palazzo Dall’Armi Marescalchi, a 500-year-old palace named for the merging of two wealthy families who acquired it in the 1600s.

Ordinarily, you can’t get in to see the place. But we sneaked in with guests attending a lecture on the 100th anniversary of the office there that oversees the region’s art and architecture, the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio.

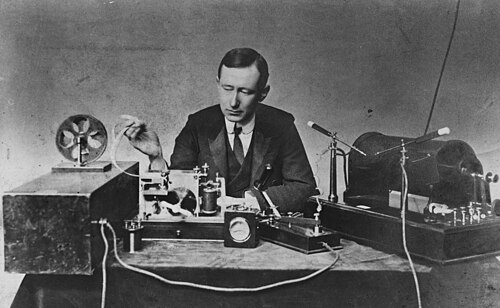

A women named Adele, who works for that office, told us people often want to see where Guglielmo Marconi was born. As a mass media historian, I understand why. He shared the Nobel Prize in physics for a breakthrough in wireless technology he achieved in 1895 when he was only 21. Marconi used the science and technology of others the way Johannes Gutenberg combined existing devices of the 1440s to invent moveable-type printing. Marshall McLuhan called our media age “The Marconi Galaxy” as he called the age of print “The Gutenburg Galaxy.”

We arrived in Bologna at the Guglielmo Marconi Airport, and walked one of the city’s main streets, called Via Guglielmo Marconi. But he left the city when he was “3 or 5,” Adele told us. After that, his family moved to the huge Marconi estate about 12 miles northeast of Bologna.

Villa Griffone was too remote for me to visit. The website said it was open only by appointment, and only for group tours.

But the Palazzo where he was born and the Villa where he experimented with electrical equipment as a teenager tell you that this was no ordinary Nobel Prize-winning scientist. Marconi was an aristocrat on both sides of his family. His father, Giuseppe, owned productive tracks of agricultural land in the area, and his mother, Annie, was a wealthy Irish lady, granddaughter of the Jameson Irish Whiskey founder. So Marconi, the boy, was raised rich and privileged in both Italian and English cultures. He had private tutors in chemistry and engineering at home.

Science and electricity interested him most of all. A physics professor who took him on in Bologna, Augusto Righi, had written about Heinrich Hertz’s discovery of electromagnetic radiation – the magic of electricity as James Clerk Maxwell revealed it, but freed from wires. What was this stuff invisible in the air like some new Holy Ghost?

The vision of wireless telegraphy obsessed the young Marconi up in his attic in the family villa.

Tomorrow, I’ll write about my interview with Barbara Valotti, who is in charge of the guided tours of the villa and the historic Marconi lab.

Leave a comment