Of several museums we have seen in our three weeks in Italy, none moved me so much as the one with the least variety or clutter.

The Museo Provincial Sigismondo Castromediano, or simply, the Provincial Museum of Lecce, is a minimalist white-walled design that spirals up one floor, like a small Guggenheim or Atlanta’s High Museum.

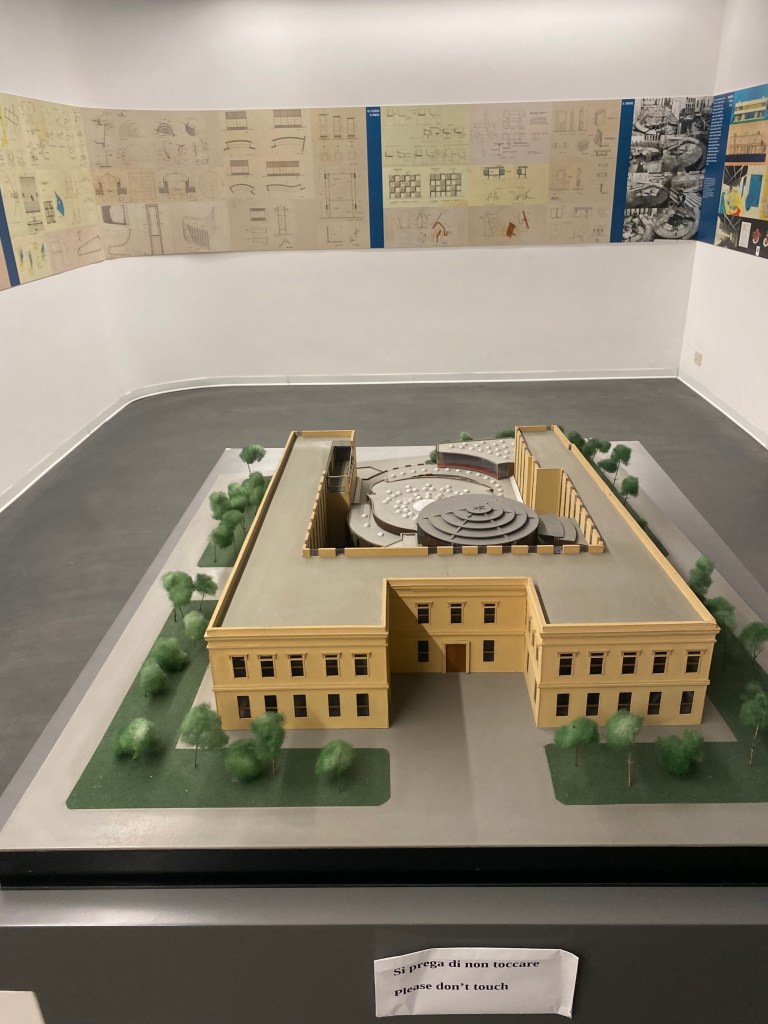

It sits just outside the old city walls, and unlike the other museums (even some churches, unless you’re attending Mass), it’s free. The modern part is tucked inside a huge 19th century palace, where the Provincial Museum began in 1868, making it Lecce’s oldest museum.

Most of the artifacts we saw came from sunken ships around the Mediterranean. As the slightly poetic English translation beside the glass cases put it, more ships rest underwater than sail on the surface. For centuries, classical Greek and Roman culture flourished on these waters, trading in oil and wine. And ideas, as another interpretative sign put it.

The ship containers were mostly amphoras, those bulbous vases that seem so inconveniently shaped. We’re taught that the pointed bottom is for sticking in the desert sand. But around the rocky Mediterranean, the shape was because amphoras could be stacked in a ship’s hold, side by side and in layers. Hundreds of these are in the museum, along with beautiful Greek vases, Iron Age hardware and other plunder from the sea floor.

The story told by the artifacts, up to a medieval church screen and a quirky variety of modern chairs, was the story of Human Time (and what about Time, I’m thinking, is not human?).

Pardon me for a condensed think-piece here, but this is why I found this museum so moving.

We earthlings evolved over millennia, yes. But in the time covered by this museum, I’m thinking that virtually all of our evolution was in technology and climate, not in the human mind or body. The evidence we have suggests we’re pretty much the same now as we were 5,000 or 10,000 years ago. Only our tools, communication media and climate have changed.

Yuval Noah Harari, the history professor at Hebrew University who wrote the popular book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, has written more recently about the challenge of Artificial Intelligence, or what he calls Alien Intelligence. In Nexus: A History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI, he argues that the human mind has two basic modes, storytelling and factual information – myth and objective truth. He worries about the “storytelling” part, for it can be filled with the kind of nonsense that demagogues like Trump can use to sway democratic mobs.

But Harari also recognizes that “storytelling” broadly conceived is what binds us together and creates culture, institutions, law, money, religion, virtually everything except the objective “facts” of science and math.

The dilemma, or balance, is depicted well in the new “Knives Out” movie on Netflix, “Wake Up Dead Man.” (I confess, we’ve been watching an English language movie almost every night.)

The Daniel Craig detective, Benoit Blanc, is “a proud heretic. . .I kneel at the altar of the rational.” He wants no storytelling, mythologizing or miracles to help him solve the murder of a grotesque power-mad Catholic monsignor. The young Father Jud, who was assigned to the parish church to help save it, first encounters Blanc when he barges into the sick church after the murder.

“Are you open?” Detective Blanc asks (a sharp double meaning).

“Always,” the young priest says, and means it in both senses.

Fr. Jud, a compassionate listener, asks Blanc, How does this church make you feel?

“Make me feel?” Blanc scoffs, dedicated to overcoming feelings with facts. “Truthfully?”

“Sure,” Fr. Jud says.

“Well, the architecture. . .the grandeur, the intended emotional effect. . .It’s like someone has shoved a story at me that I do not believe, that’s built upon the empty promise of a child’s fairytale that’s filled with malevolence and misogyny, homophobia, justified violence while hiding its own shameful acts. It’s like an ornery mule kicking back.”

You notice that Blanc is getting quite emotional, while Fr. Jud listens with a certain knowing smile.

Blanc continues: “I want to pick it apart and pop its insidious bubble of belief and get to a truth I can swallow without choking.”

Fr. Jud: “You’re being honest. It’s good.”

Blanc thinks he’s waking up the naïve priest. “Telling the truth can be a bitter herb,” he says. “I suspect you can’t be honest with your parishioners.”

“You can always be honest by not saying the unhonest part.”

Then Fr. Jud has an answer that I think goes to Harari’s idea of human “storytelling,” and helps me with all these Baroque Italian churches.

“You’re right, it’s storytelling,” he says, and admits this 19th century gothic church in New York has more in common with Disneyland than with Notre Dame.

“The question is, do these stories convince us of a lie, or do they resonate with something deep inside of us that’s profoundly true. . . that we can’t express any other way, except storytelling.”

Blanc looks interested, but baffled. He has no counter argument. “Touché, Padre.”

The Provincial Museum had a story to tell that was about the evolution of our technology – shipping, trading, weaponry. And before any of that, the most important of all – the alphabet.

For more than a thousand years, Sumerian and Egyptian cultures experimented with incisions in tables with symbolic meaning. But the breakthrough was around the 8th century B.C.E., when a simple and phonetic alphabet conveyed spoken language.

The top of the museum’s spiral had one final display, a column with one of these “alphabeteries” encased in glass. It was originally found in the tiny promontory at the southern tip of Italy’s bootheel, a town called Patù. If “Mediterranean” means middle of the earth, Patù must be the middle of that, and the middle of Time.

“The alphabet is certainly one of the greatest inventions of man, which was made once and for all on the Eastern Mediterranean shores at the end of the second millennium B.C., . . the perfect machine,” says the interpretive sign. “The testimonies [of its evolution] come from the past in the form of inscriptions, the ‘alphabeteries,’ in which someone traced the graphic model so that other people, properly guided, could learn it.”

“The Patù column is one of the most mysterious and remarkable of them all.”

Leave a comment