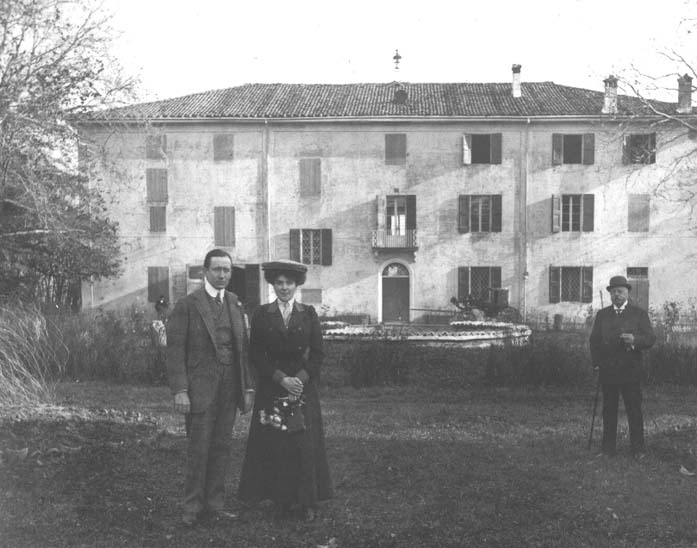

The boy who had it all . . . wanted more. The young Gulielmo Marconi, living with his wealthy family in an Italian villa amid green pastures and woods, dreamed of bringing countries together.

This was in the 1890s. The university city of Bologna, which seemed far away at 15 kilometers, was only one place that Guliemo thought about bringing into closer touch with the other great cities of the world. He thought about bringing together even the earth’s remote spots – and his home, Villa Griffone, seemed pretty remote to him.

“It was all so vague,” the famous pioneer of wireless radio communication recalled in 1912. “As nearly as I can put that far-off ambition into words, it seemed to be that I wanted to engage in some form of scientific work that would keep me traveling.”

Marconi died in 1937 at age 63.

Today, the family mansion in Italy is a museum, with the pastoral landscape preserved around it. Barbara Valotti, who directs the tours there, described in a phone interview with me the role of Marconi in developing the world-changing technology of wireless telegraphy. This eventually made possible TV and Wi-Fi.

Other scientists were working on the same ideas and providing much of the technology Marconi used. But what distinguished Marconi, mostly, was his early start. He began experimenting with electricity at age seven.

At 18, he built a battery that was entered into an international science competition. The following year, he began transmitting wireless signals out of his home’s attic window to antennae that he set farther and farther away, beyond the line-of-sight hill.

“He was so determined,” Valotti said, “not only scientific, but also technical and commercial.”

Valotti also provided me with the digital scan of a remarkable front page of Part II (Miscellany and Art) of the New York Herald-Tribune of April 14, 1912. The page was entirely taken up with an article and drawings from an interview of Marconi in London’s Holland House by a Herald-Tribune caricaturist pen-named “Kate Carew.”

“Your old Aunt Kate” writes playfully about the interview, around her sketches, and gets Marconi to confess that he always believed excessively in himself, “dreamed I was going to be somebody – make the world talk.”

Another remarkable thing about this article is that it appeared on the very day that the brand new luxury ship Titanic stuck an iceberg on its way across the Atlantic. The wireless telegraph for the ship was provided by the Marconi Co.

Other ships had wireless operators by then as well. Just three years earlier, the RMS Republic was rescued after a collision in fog off the Massachusetts coast, thanks to its wireless SOS signal. Kate Carew asked Marconi how he felt about those lives being saved by wireless telegraph. “In my imagination it had happened a thousand times, so when the reality came it meant nothing except the gratification at the saving of life.”

So on April 14, 1912, other ships had warned the Titanic about icebergs in the area. But no other wireless telegraphy for ships was as powerful as Marconi’s, which could reach 1,000 miles. The only ship close enough to rescue Titanic passengers, The California, was 10 miles away but was unaware. The telegrapher had turned off its system because the Titanic’s telegrapher had complained about interference with its signals.

Approximately 2,200 souls were lost at sea early the next morning.

The interference of signals in that disaster led Congress, within months, to pass the 1912 Radio Act, which required licensing of commercial and amateur radio stations. It also led to ships having designated channels and trained wireless telegraph operators.

That set in stone the concept of airwaves belonging to the public, to us, for the public good. It’s why the federal agency that became the FCC grants (or not) broadcast licenses. Entertainment dominated, but the licensing was for the Public Interest, in theory anyway.

In a way no one could have predicted, Marconi’s dream of connecting the world succeeded.

Leave a reply to ecstaticb9d8b4c994 Cancel reply